I was thinking about women in tech, it being December and as I write this draft, one day post the anniversary of the Montreal massacre at École Polytechnique.1 14 women engineering students gone. RIP.

There was also the very recent and unfortunate (to put it mildly) IBM ‘s hairdryer hackathon blunder, 2 serving as a reminder that women still ain’t got no respect.

So I thought to write a tribute post to Ada Lovelace, born exactly two hundred years ago on December 10th, 1815. Daughter of poet Lord Byron and arguably, the first computer programmer, she was—in a word—brilliant. Her parents split up when she was a baby, and her mother seems to have not regarded her ex the poet in the best light, and so encouraged Ada to study mathematics, so as to not follow in her father’s romantic (and insane3) footsteps.

She took to it well, eventually collaborating with Charles Babbage (mathematician, philosopher and inventor). In 1842 she translated from French L.F. Menabrea’s paper about Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine (an “early mechanical general-purpose computer”). Her own notes on the engine include what is recognised as the first algorithm intended to be carried out by a machine. Because of this, she is often regarded as the first computer programmer “The paper ends with the famous “Note G”, in which she analyzes an algorithm for calculating Bernoulli numbers and shows the code for it on the (never built) machine”.4

Which is all to say, she was no slouch in the brains department.

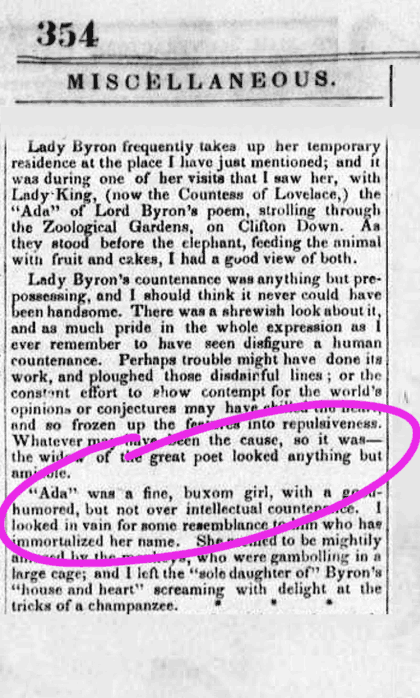

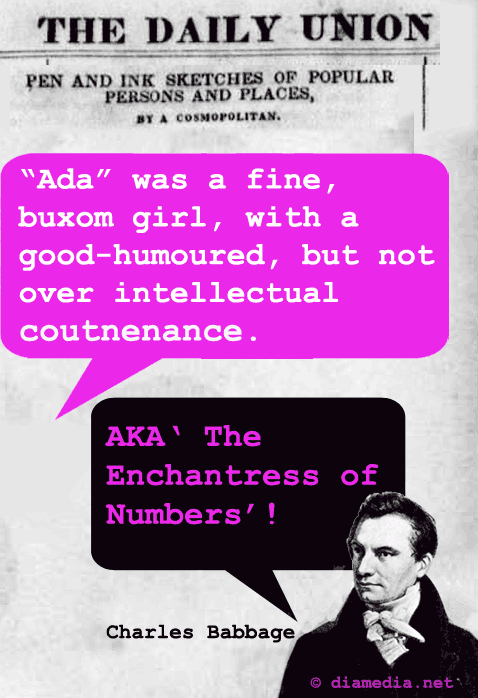

If we think that the STEM community (Science, Technology, Engineering , Math) hasn’t yet caught up with the face that woman are essential and critical members of the technosphere and beyond, then one wonders what it must have been like Ada her back in the day. I searched through the Library of Congress American newspaper archives and all I could find was one(!) reference to her. And it’s not about her mathemtical achievement. The Daily Union from 1845, a few years after her collaboration with Charles Babbage, reports her (at 29 years old) as being a “fine, buxom girl, with a good-humoured, but not overly intellectual countenance”.

I’ve only done preliminary research into her life, but she apparently was following her father’s footsteps in at least one sense — she gives a poetic slant to how the engine might compose music.

“Again, it [the Analytical Engine] might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations, and which should be also susceptible of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism of the engine . . . Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent.”5

She died young, at 36, and requested to be buried next to her father.